The basketball world first got to know Kevin Garnett as an asterisk.

By the time he had wrapped up his 21-season NBA career, though, Garnett had shown he was way more of an exclamation point.

There was no guarantee when Garnett raised his hand in the spring of 1995 and took his chances as the first high school player in 20 years to enter the NBA Draft. No one had done it in 20 years, with Darryl Dawkins and Bill Willoughby generally rendered as footnotes in league history, their careers largely inconsequential.

Had Garnett failed — had he come in too soon, without a year or three playing college basketball to grow into his lanky, athletic, 6-foot-11 frame — he might have washed out after a few short seasons, with whatever was left of a three-year, $5.6 million contract in his pocket. The 19-year-old out of Chicago’s Farragut Academy would have been a cautionary tale to those who followed, maybe flashing a big red light to precocious teenagers such as Kobe Bryant, Dwight Howard and LeBron James.

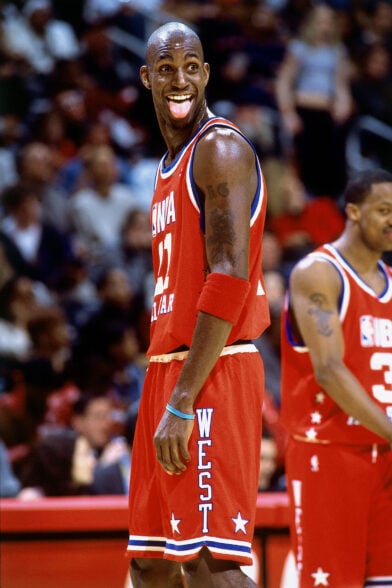

Only Garnett did not fail. He blazed along his learning curve for the Minnesota Timberwolves, a team so down on their luck they didn’t blink at the prospect of selecting such a raw, young talent. By Year 2, Garnett was an All-Star bound for the NBA playoffs. He would become a Most Valuable Player, the league’s best defensive player at his peak, a 15-time All-Star, an Olympic gold medalist, a champion and eventually a Hall of Famer.

Along the way, the kid from Mauldin, S.C., revealed himself to be one of the league’s most joyful performers, morphing into an all-time ferocious competitor. Garnett made his presence felt from the mosh pit beneath the rims all the way to the nosebleed seats upstairs.

No asterisk. All exclamation point.

In the beginning, there was skepticism. Criticism. Testing and even some hazing.

In the beginning, there was skepticism. Criticism. Testing and even some hazing.

In Garnett’s first NBA preseason, Milwaukee’s Glenn Robinson butt-bumped the Timberwolves’ rookie out of bounds. Lakers forward Cedric Ceballos scored against him, then broadly shook his head side to side and said, “He ain’t ready.”

Even Garnett’s new teammates in Minnesota went hard at the kid. This was back in 1995, when contracts weren’t as big or always guaranteed, and no veteran wanted to lose a roster spot to somebody who should have been a college freshman somewhere. The cover story, though, when Sam Mitchell and Doug West shoved Garnett into the bleachers during scrimmages in that training camp was that they wanted to toughen him up NBA-style and fast-track his development.

Garnett took it. He didn’t break, he didn’t say boo. In a matter of weeks, the scaffolding came off and the curtain on his pro career was raised.

One thing quickly became clear about the 19-year-old: He didn’t need to have his hand held.

An early plan to have Garnett move in with, or at least assign him to regular check-ins with a surrogate family in the Twin Cities got nixed immediately. So did the idea of having Garnett spend time with Golden Gopher players from the University of Minnesota.

Garnett’s mom and sisters would rotate through, but mostly he was on his own, working a new job in a new city, only with a higher profile than most high school grads. He had his teammates, certainly. Oh, and those close buddies from back home, buzzing through the streets of Garnett’s subdivision in go-karts the budding Wolves star had purchased.

As the 1995-96 season played out, Minnesota VP Kevin McHale, a former Boston Celtics Hall of Fame power forward, fired coach Bill Blair and handed GM Flip Saunders the keys to both the team and Garnett.

Saunders’ approach with the rookie? Give him as much leash as he could handle. That wound up being a lot of leash. In a January game against Houston at Target Center in downtown Minneapolis, Garnett staged a coming-out party off the Wolves bench, zapping the crowd with his exuberant plays at both ends.

After that one, he dubbed himself “Da Kid” and vowed bigger and better. As winter turned to spring, that’s what he delivered. Have you heard of shaky MLB batters who can’t “hit their weight” in batting average? Garnett began to regularly outscore his age.

When Shaquille O’Neal couldn’t make it to Cleveland for All-Star Weekend in Feb. 1997 because of an injury, it was notable because the Los Angeles Lakers’ 24-year-old center was one of only three honorees not to be present for the NBA’s 50th Anniversary celebration. Lakers great Jerry West (surgery) and the late court magician Pete Maravich were the other two.

When Shaquille O’Neal couldn’t make it to Cleveland for All-Star Weekend in Feb. 1997 because of an injury, it was notable because the Los Angeles Lakers’ 24-year-old center was one of only three honorees not to be present for the NBA’s 50th Anniversary celebration. Lakers great Jerry West (surgery) and the late court magician Pete Maravich were the other two.

Named as O’Neal’s replacement? That’s right, Garnett. The second-year player, now 20, found himself mingling with the game’s legends, from Wilt Chamberlain and Julius Erving to George Mikan and Moses Malone. Obviously there were plenty of current NBA stars and a few of Garnett’s peers on hand that weekend. But the players from yesteryear were the ones getting most of the attention from the fans, the media and the ’97 All-Stars.

Five members of that select Top 50 played in Sunday’s game: Michael Jordan, Scottie Pippen, Hakeem Olajuwon, John Stockton and Karl Malone. Two more guys who had spent much of the weekend in awe and shaking hands – Garnett and Gary Payton – would find themselves a quarter-century later on a list that had grown to the Top 75.

By the ripe old age of 25, Garnett had logged six NBA seasons, compared to the two or three he might have played with a more traditional arrival. He had handled everything thrown his way, on and off the court. His youthful enthusiasm still was evident, even as his intensity began to separate him more and more from his peers.

Banging the ball against your forehead to force more focus at the foul line or headbutting the padding on the basket stanchion as a pre-game psych — who does that? Garnett did. His chest thumps, pulling his jersey to “show” his heart, slapping the floor, in later years cranking an impromptu set of push-ups … all of it became signature traits (eagerly imitated by other players) of one of the league’s most watchable and entertaining performers.

As the NBA moved into the new century – the 2000s — Garnett seemed to have it all: A game worth flaunting and a charisma to draw in even casual hoops fans. He and Wolves point guard Stephon Marbury were being pitched almost from their start as an updated version of Stockton & Malone. Together — big and little, inside and outside, playmaker and post-up — the two young Minnesota stars seemed to have the basketball world at their feet.

As the NBA moved into the new century – the 2000s — Garnett seemed to have it all: A game worth flaunting and a charisma to draw in even casual hoops fans. He and Wolves point guard Stephon Marbury were being pitched almost from their start as an updated version of Stockton & Malone. Together — big and little, inside and outside, playmaker and post-up — the two young Minnesota stars seemed to have the basketball world at their feet.

All they needed to do from there was stay together and win.

Well, they didn’t stay together. Marbury forced his way out, All-Star forward Tom Gugliotta left and Garnett began flipping through a Rolodex of teammates. The results through his first eight pro seasons had a good-news bad-news feel to them.

The good was seven consecutive playoff appearances for a franchise that had been 240 games under .500 in the six seasons before he arrived. The bad was that every time they reached the postseason, Minnesota and Garnett would go splat! They failed to get out of the first round each time.

By the 2003 offseason, everybody’s patience, inside and outside the organization, was wearing thin. So McHale rolled the dice to acquire two salty veterans, wing Latrell Sprewell and point guard Sam Cassell. Both had had turbulent stretches with their previous teams, but their talent was undeniable and best of all, they clicked with Garnett.

The 2003-04 season became one big joyride, with the trio gracing the cover of Sports Illustrated and leading Minnesota to the NBA’s best record of 58-24. Garnett did win the actual MVP, and the Timberwolves won not one but two playoff series.

OK, so Cassell got hurt and they couldn’t beat the Lakers in the Western Conference Finals. But both No. 21 and the franchise experienced their finest moment to that point in that Game 7 semifinal victory over Sacramento.

Let’s pause for an appreciation of the many facets of Garnett’s game. His versatility made him one of the NBA’s all-time Swiss Army knife performers, capable of stints at all five positions, either end. He was early in a trend of star “power forwards” who eschewed the idea of playing center, the position to which most would have been relegated in a previous generation thanks to height and coaches’ expectations. There were a bunch who arrived in the span of a few years, including Garnett, Chris Webber, Rasheed Wallace, Antonio McDyess, Shareef Abdur-Rahim and Tim Duncan.

Old school, they would have found themselves playing with their backs to the basket, banging for post-up position for however long they were on the court. Not nearly as much fun, in other words, as how they actually got used: Facing the basket, extending their shooting range, putting the ball on the floor, some even venturing as far out as the 3-point line. They were “stretch fours” before there was a term for it.

Garnett’s passing ability, particularly finding teammates in close quarters inside, could be jaw-dropping. Hitting the 7-foot mark soon after his NBA arrival, he still could put up Larry Bird-like numbers across the board, with six consecutive seasons averaging at least 20 points, 10 rebounds and five assists.

It tells us a lot about Garnett’s priorities and sensibilities that so many of his highlights came from the defensive end. He was a tireless rim protector and savvy help defender, but he was active enough to put up numbers there, too. Consider this: Six seasons in which he amassed at least 100 blocks and 100 steals, something neither Bird nor Tim Duncan ever managed.

At 31, Garnett began a new, second phase of his career. And the reboot came in Boston.

Garnett had to be convinced to leave Minnesota and it took a package of five players and two first-round picks for the Celtics to land him. Sharpshooter Ray Allen had come aboard too, joining the popular Paul Pierce in what became arguably the first “super team” of the current millennium. And that Boston team was pretty super, right out of the gate.

With its Big Three 2.0 — a variation of the Bird, McHale and Robert Parish teams in the 1980s — the Celtics raced to a 29-3 record. Garnett, Pierce and Allen divvied up their duties perfectly: Garnett in charge of defense and rebounds, Allen pulling opponents to 3-point territory, and Pierce working the mid-range and clutch minutes.

Coach Doc Rivers introduced an African ethos called “ubuntu” to draw the group tight, and by season’s end, the 66-16 Celtics had won the Atlantic Division by 25 games. The postseason brought some hiccups — Boston needed seven games each to beat Atlanta and Cleveland — but once it got past Detroit, there seemed to be some destiny and ghosts in the rafters kicking in for the Finals.

The Celtics beat the Lakers in six, outscoring them by 50 points overall for the franchise’s 17th championship banner. And Garnett’s redemption.

Garnett played five more seasons for the Celtics before finishing up with pit stops in Brooklyn and back in Minnesota. Along the way, Garnett won the admiration of one of the NBA’s greatest players.

Bill Russell, besides being a Celtics’ icon, saw in the younger man a kindred spirit in how – and how hard – he played. Both built their games on defense, Russell triggering so many great teammates to 11 titles in 13 seasons, Garnett being named Defensive Player of the Year for 2007-08 (an award that didn’t exist in Russell’s era).

For Russell, though, it went beyond game respecting game. He appreciated Garnett’s appreciation of Celtics traditions. The reverence he showed in his wearing of “the Green.” And the fire that burned inside him to win. Not as frequently as Russell, of course, but it was evident every night.

That’s what made anything possible.